-

-

-

Total:

-

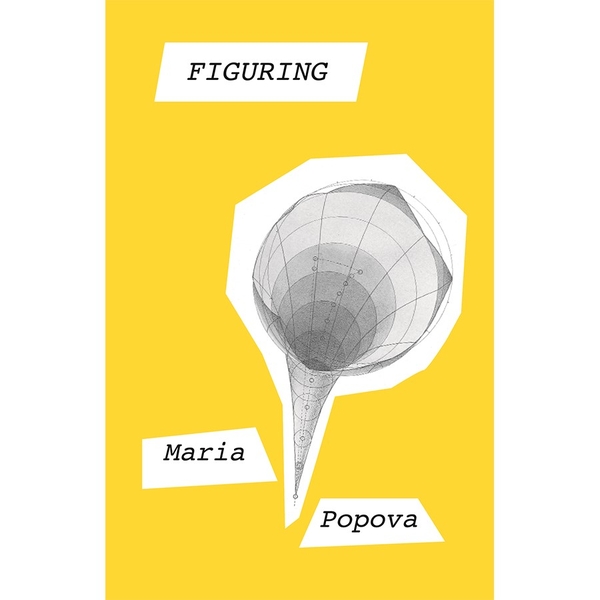

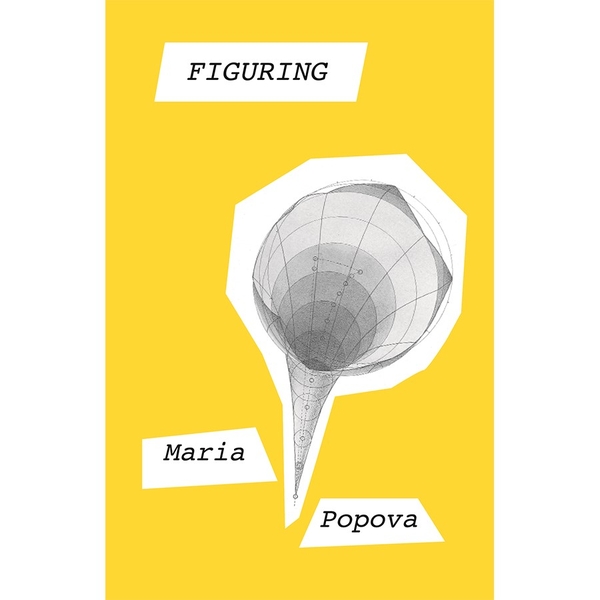

Figuring

11/11/2021

Rin

Tôi vừa viết xong một quyển sách. Nó được đánh đổi bởi 12 năm của Brain Picking và những trải nghiệm đẹp đẽ, khó khăn, lộn xộn nhất của cuộc sống cá nhân của tôi.

Figuring đào sâu khám phá sự phức tạp, đa dạng, và mâu thuẫn của tình yêu, và công cuộc của con người đi tìm kiếm sự thật, ý nghĩa và sự siêu nghiệm, qua một chuỗi đan xen các câu chuyện cuộc đời của vô số nhân vật lịch sử qua bốn thế kỷ - bắt đầu với nhà thiên văn học Johannes Kepler, người tìm ra quy luật của sự chuyển động của các hành tinh, và kết thúc với nhà sinh vật học biển Rachel Carson, người đã đóng góp vào việc làm gia tăng các phong trào bảo vệ môi trường. Giữa những nhân vật này là một loạt những nghệ sĩ, cây viết, và nhà khoa học – đa số là phụ nữ, đa số đồng tính luyến ái – những người đã vượt lên những mối quan hệ bí mật không thể phân loại và thường là đau khổ của họ để đóng góp cho cộng đồng và giúp chúng ta thay đổi cách hiểu, trải nghiệm, và trân trọng vũ trụ. Một trong số họ là nhà thiên văn học Maria Mitchell, người đã mở đường cho phụ nữ làm việc trong khoa học; nhà điêu khắc Harriet Hosmer, người cũng làm việc tương tự trong nghệ thuật; nhà báo và phê bình văn học Margaret Fuller, người khuấy động phong trào nữ quyền; và nhà thơ Emily Dickinson.

Cuộc đời của họ đã đặt ra những câu hỏi lớn về thước đo cho một cuộc sống tốt và ý nghĩa của việc để lại một dấu ấn tốt đẹp khó phai trên thế giới bất hảo này: Thành tựu và sự tán dương có đủ để tạo nên hạnh phúc? Hay là sự thiên tài? Hay tình yêu? Đan xen trong câu chuyện là những nhân vật ngoại vi – Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Darwin, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Herman Melville, Frederick Douglass, Caroline Herschel, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman – và một tấm thảm được thêu dệt nên bởi các chủ đề về âm nhạc, nữ quyền, lịch sử của khoa học, sự vươn lên và lụi tàn của tôn giáo, và cách mà sự giao thoa giữa thiên văn học, thơ ca và triết học Thuyết tiên nghiệm đã khích động các phong trào bảo vệ môi trường.

Cách đây rất lâu, một phóng viên tốt bụng đã hỏi tôi tại sao tôi thường xuyên từ chối những lời đề nghị viết các thể loại sách đơn giản, dễ tiếp thị mà tôi thường hay tiếp cận. Tôi trả lời (xin đừng phán xét: hồi đó tôi mới ở tuổi hai mươi) rằng tôi không hứng thú với việc ném ra ngoài thế giới một cuốn sách có tuổi thọ của một quả chuối. Tôi mong muốn Figuring sẽ được ở trên kệ sách đến cuối đời nó.

Đây là phần mở đầu – chapter 0 trên 29:

“All of it — the rings of Saturn and my father’s wedding band, the underbelly of the clouds pinked by the rising sun, Einstein’s brain bathing in a jar of formaldehyde, every grain of sand that made the glass that made the jar and each idea Einstein ever had, the shepherdess singing in the Rila mountains of my native Bulgaria and each one of her sheep, every hair on Chance’s velveteen dog ears and Marianne Moore’s red braid and the whiskers of Montaigne’s cat, every translucent fingernail on my friend Amanda’s newborn son, every stone with which Virginia Woolf filled her coat pockets before wading into the River Ouse to drown, every copper atom composing the disc that carried arias aboard the first human-made object to enter interstellar space and every oak splinter of the floor-boards onto which Beethoven collapsed in the fit of fury that cost him his hearing, the wetness of every tear that has ever been wept over a grave and the sheen of the beak of every raven that has ever watched the weepers, every cell in Galileo’s fleshy finger and every molecule of gas and dust that made the moons of Jupiter to which it pointed, the Dipper of freckles constellating the olive firmament of a certain forearm I love and every axonal flutter of the tenderness with which I love her, all the facts and figments by which we are perpetually figuring and reconfiguring reality — it all banged into being 13.8 billion years ago from a single source, no louder than the opening note of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, no larger than the dot levitating over the small i, the I lowered from the pedestal of ego.

How can we know this and still succumb to the illusion of separateness, of otherness? This veneer must have been what the confluence of accidents and atoms known as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., saw through when he spoke of our “inescapable network of mutuality,” what Walt Whitman punctured when he wrote that “every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

One autumn morning, as I read a dead poet’s letters in my friend Wendy’s backyard in San Francisco, I glimpse a fragment of that atomic mutuality. Midsentence, my peripheral vision — that glory of instinct honed by millennia of evolution — pulls me toward a miraculous sight: a small, shimmering red leaf twirling in midair. It seems for a moment to be dancing its final descent. But no — it remains suspended there, six feet above ground, orbiting an invisible center by an invisible force. For an instant I can see how such imperceptible causalities could drive the human mind to superstition, could impel medieval villagers to seek explanation in magic and witchcraft. But then I step closer and notice a fine spider’s web glistening in the air above the leaf, conspiring with gravity in this spinning miracle.

Neither the spider has planned for the leaf nor the leaf for the spider — and yet there they are, an accidental pendulum propelled by the same forces that cradle the moons of Jupiter in orbit, animated into this ephemeral early-morning splendor by eternal cosmic laws impervious to beauty and indifferent to meaning, yet replete with both to the bewildered human consciousness beholding it.

We spend our lives trying to discern where we end and the rest of the world begins. We snatch our freeze-frame of life from the simultaneity of existence by holding on to illusions of permanence, congruence, and linearity; of static selves and lives that unfold in sensical narratives. All the while, we mistake chance for choice, our labels and models of things for the things themselves, our records for our history. History is not what happened, but what survives the shipwrecks of judgment and chance.

Some truths, like beauty, are best illuminated by the sidewise gleam of figuring, of meaning-making. In the course of our figuring, orbits intersect, often unbeknownst to the bodies they carry — intersections mappable only from the distance of decades or centuries. Facts crosshatch with other facts to shade in the nuances of a larger truth — not relativism, no, but the mightiest realism we have. We slice through the simultaneity by being everything at once: our first names and our last names, our loneliness and our society, our bold ambition and our blind hope, our unrequited and part-requited loves. Lives are lived in parallel and perpendicular, fathomed nonlinearly, figured not in the straight graphs of “biography” but in many-sided, many-splendored diagrams. Lives interweave with other lives, and out of the tapestry arise hints at answers to questions that raze to the bone of life: What are the building blocks of character, of contentment, of lasting achievement? How does a person come into self-possession and sovereignty of mind against the tide of convention and unreasoning collectivism? Does genius suffice for happiness, does distinction, does love? Two Nobel Prizes don’t seem to recompense the melancholy radiating from every photograph of the woman in the black laboratory dress. Is success a guarantee of fulfillment, or merely a promise as precarious as a marital vow? How, in this blink of existence bookended by nothingness, do we attain completeness of being?

There are infinitely many kinds of beautiful lives.

So much of the beauty, so much of what propels our pursuit of truth, stems from the invisible connections — between ideas, between disciplines, between the denizens of a particular time and a particular place, between the interior world of each pioneer and the mark they leave on the cave walls of culture, between faint figures who pass each other in the nocturne before the torchlight of a revolution lights the new day, with little more than a half-nod of kinship and a match to change hands.”

Figuring được xuất bản ngày 2 tháng 5 năm 2019, với trang bìa được thiết kế bởi nhà thiết kế tài hoa Peter Mendelsund, sử dụng hình ảnh minh họa cho ý thức bằng toán học mà tôi đã phải lòng từ lâu – một trong những tác phẩm của nhà tâm lý học thế kỷ 19 ở New Zealand Benjamin Bett “tâm lý học hình học”

__________________________

Bài viết gốc: Figuring - Maria Popova

Dịch bởi The Bookshelf Hanoi